an analysis of the rising cost of education in australia

(extract)

abstract

human capital, or a better educated labour force, is a major determinant of economic growth and productivity. however, recent trends in the cost of education in australia may cause growth and productivity to suffer. for example, during the period 1982-2003 inflation rose on average by 4.4 per cent per annum, whereas the cost of education grew overall on average by 7.8 per cent. this has made education a relatively expensive item among australian households. this paper compares and contrasts the cost of education in australia and comparable economies with the cost of other goods and services embedded in the cpi(consumer price index)basket using the latest available quarterly data. finally, the major determinants of the rising cost of education in australia are examined. it is found, inter alia, that over the period 1986-2003 the increasing number of students enrolled at non-governmental primary and secondary schools and the introduction of the higher education contribution scheme(hecs)were major influences on the rising cost of education, explaining some 98 per cent of variation in the cost of education in australia over time.

1. introduction

there is a consensus among economists that human capital plays a substantial role in achieving higher economic growth and increased labour productivity. new growth theories identify the channels through which economic growth occurs and how reform processes can stimulate the rate of investment in physical capital, human capital, technological know-how and knowledge capital. together these factors exert a sustained and positive effect on the long-run growth of the economy (rebelo,1991).for instance, in their seminal work barro(1991)and barro and lee(1994)echoed the importance of human capital(or a better educated labour force)as a major determinant of economic growth and productivity. more recently, valadkhani (2003)found, inter alia, that long- term policies aimed at accelerating the various types of investment in human capital will also improve labour productivity. as higher productivity translates directly into higher per capita income, australians, as a whole, benefit from higher standards of health care, education and public welfare. very recently, chou(2003,p397)found that“42 per cent of australian growth between 1960 and 2000 is attributable to the rise in educational attainment”. therefore, it is important to monitor the cost and affordability of education through time. however, compared with the price of most other goods and services, it would appear that the cost of education in australia has been increasing at an alarming rate. moreover , with similar trends witnessed in both the united kingdom and the united states, it seems that australia is not the only developed country that has experienced this phenomenon.

a better educated workforce will almost certainly have higher income in the future and so we do not take issue in this paper with the increasing role of the private funding of educational expenses. it is clearly self-evident that the indefinite provision of “free” education by the various tiers of government, through collecting taxes from the society as a whole, is neither equitable nor sustainable into the future. however, given the higher income levels for graduates and the positive externality(or public benefits)associated with a better educated workforce for society, costs should desirably be split between the taxpayer and the student in some sort of optimal manner. in the context of higher education, the important point is that students studying in areas yielding substantial social benefits-but perhaps associated with relatively low market income-should have access to interest-free, income-contingent loans as well as government direct funding for at least some portion of their study cost. however, if their areas of study are highly marketable(e.g. law and medicine),they may have limited access to such loans(king,2001,p.192).nevertheless, the funding of schools and universities remains one of the most vigorously debated issues in australia. it is interesting to note that the total operating revenue of the 40 higher education institutions in 2002 was$11.6 billion of which 16 per cent was collected through hecs and 41 percent(54 percent in 1997)financed by commonwealth government grants(department of education, science and training,dest,2002,p.3).similarly, in 1997 the commonwealth and state governments altogether funded:(i)up to 95 per cent of revenue for government schools; and(ii) 56 per cent of revenue for non-government primary and secondary schools(borthwick,1999,p.1).

of course, at the outset, it should be noted that purchasing power parity studies indicate services are often more expensive in rich countries than in poor countries(see, inter alia, dowrick, 2001,and oecd,2001)and so one might expect a labour intensive service like education to be increasing in relative price as the country grows. more broadly, baumol(1997)also argues that the rising cost of labour-intensive industries, such as the arts, health care, and education, is inevitable. price rises in service industries can therefore be expected to be higher on average than the inflation rate for the economy as a whole.

furthermore, the rising rate of public-sector inflation can be explained by “the low productivity of labour-intensive government activities compared with the relatively capital- intensive private sector”(fordham,2003,p.574).more specifically gundlach and w? βmann (2001)examined changes in the productivity of schooling for six east asian countries, supporting the view that the price of schooling rose by more than the price of other labour-intensive services in 1980 to 1994.the rising price of schooling can be attributed to declining relative productivity in schooling. according to gundlach and w?βmann, the fading productivity of schooling in east asian countries relates to a marked decline in the pupil-teacher ratio.

therefore, it is important to note that it is quite normal that services such as education probably can be expected to become more expensive for an advanced country such as australia. however, it nonetheless remains a useful exercise to investigate to what extent the cost of education has been increasing and what may be the possible causes of this rise.

the basic objectives of this paper are therefore to:(i)substantiate the extent to which the cost of education has been rising in australia and internationally; and(ii)determine the major factors contributing to such important phenomena which undoubtedly will have implications for the long-run prosperity of australia’s economy. it is not our intention to delve into alternative policy approaches which attempt to deal with the issue of the most appropriate way to fund the education system. for a detailed account of the literature on the various views on the way in which education at all levels can be financed see barr(1998),borthwick(1999), quiggin(1999),king (2001),chapman(2001)and burke and long(2002),amongst others.

2.the cost of education in australia, the uk and the us

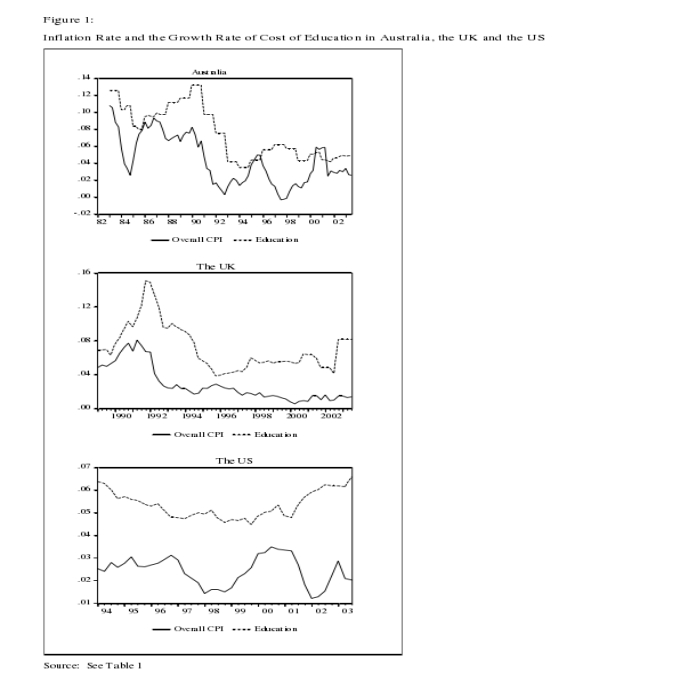

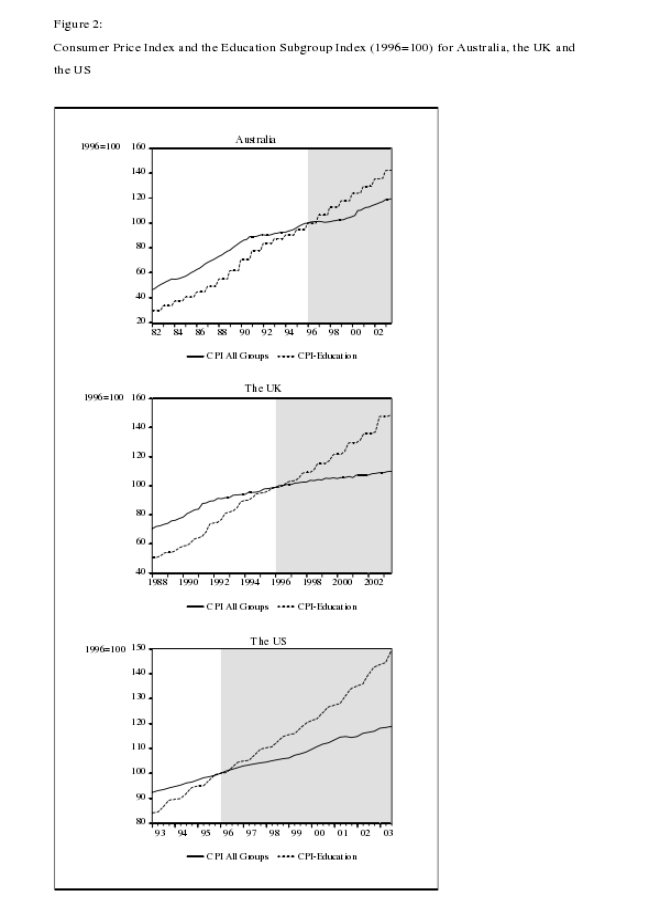

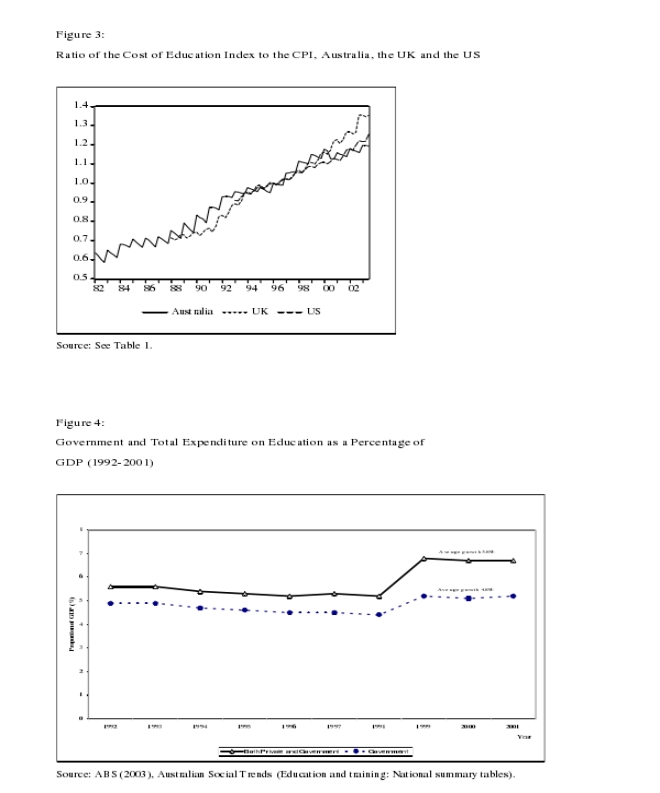

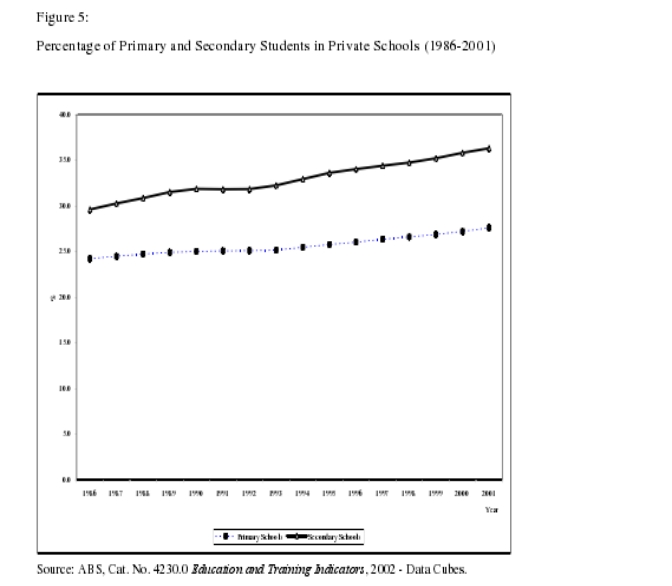

figure 1 shows that the annualised rate of increase in the cost of education,as measured by ln(p)t- ln(p)t-4,in australia, the uk and the us has almost always been substantially higher than the rate of inflation. moreover, according to figures 2 and 3,the gap between the cpi(1996=100)and the education sub-group index has been widening continuously with the passage of time, particularly in the uk and the us. from figure 4 it can be inferred that, to some extent, this growing gap may be attributed to the difference between the government and private expenses on education as a proportion of gdp compared with public funding alone. as can be seen from figure 4,over the period 1992-2001,while the average share of government expenses in gdp was around 4.8 per cent, the share of total expenses(both private and government)in gdp was 5.8 per cent, suggesting that the share of private spending on education has increased.

in a similar way, figure 5 shows that an increasing proportion of primary and particularly secondary pupils study at private schools. in 1986 about 30 per cent of secondary pupils were attending private schools, whereas in 2003 this figure reached about 35 per cent. total enrolments at both primary and secondary private schools rose by 1.7 per cent per annum over the 15 years from 1986 to 2001,compared with a more modest increase of 0.18 per cent annually for government schools.

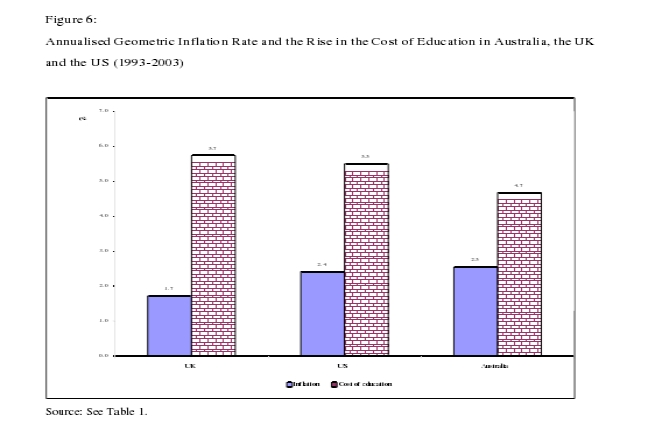

in figure 6 we present the geometric annualized average growth rate of all groups in the cpi and the education sub-group for australia, the uk and the us during the period 1993-2003. there are two reasons for selecting this particular sample period. first, consistent data were only available for all three countries over this period, and second, in the beginning of this sample period and following many other oecd countries, inflation targeting became the primary goal of australian monetary policy. in this, the reserve bank of australia is required to keep the overall rate of inflation between 2-3 percent per annum over the course of the business cycle, but with no similar commitment to keep the growth rate of any subgroup of the cpi in check. this chart lends further support that the cost of education has been growing well above inflation in these three countries over the period in question.

a cursory look at figure 6 also reveals that the annual growth rate of the cost of education in australia is relatively lower than that in the uk and the us. to some extent the difference between the growth rate of the cost of education and inflation in australia and the other two countries will be narrowed if we consider the instantaneous growth rates in lieu of the compound rates.

table 1 presents the compound and average instantaneous annualised inflation rates and the compounding annualised growth rates in the cost of education for these three countries during the same sample period(1993-2003).no matter which growth rate formula is used, in all three economies, the average growth rate of the cost of education is well above the overall inflation rate. for example, in the uk and australia, the compound(geometric)average inflation rates were 1.7 and 2.5 per cent in the period 1993-2003,respectively,whereas the corresponding rises in the cost of education in these two countries were 5.7 and 4.7 per cent. using average instantaneous growth rates the corresponding figures are 5 and 5.5 percent, respectively.

table 1 shows that the cost of education has risen between 5 and 5.5 per cent in australia, the uk and the us over the 1993-2003 periods. the difference between the compound and instantaneous growth rates relates to the fact that the latter allows for the middle observations or changeability of a series to impact on the computed average growth rate, whereas in the former (i.e. the compound growth rate)the middle observations do not play any significant role in determining the outcome. as displayed in table 1,the volatility of the quarter-by-quarter growth rate of the cost of education(as measured by the standard deviation)in australia(0.0209)is higher than those of the uk(0.0160)and the us(0.0094).therefore, it can be argued that the average instantaneous rates are more useful reflections of the changing cost of education.

3. concluding remarks

the present paper employs descriptive statistics and parametric analysis to examine the rising cost of education in australia. in common with experiences in comparable oecd economies, the cost of household education expenditure has been rising faster than the overall rate of inflation and paradoxically for the most part as fast as or faster than leading economic 'sins' (alcohol and tobacco).such trends are likely to continue in the future, and perhaps even accelerate, with the increasing proportion of primary and secondary students being educated at non-government schools and the liberalisation of contribution charges and full fee-paying quotas in the recent tertiary education reforms.

at first impression, such developments appear to pose potentially adverse impacts on human capital investment in australia and, in turn, on economic growth and labour productivity. however ,it should be remembered that the cost drivers of education in australia are, in some part, reflective of households' choices concerning education. these include the choice between private and public primary and secondary education in the present and, in the future, careful household choices concerning tertiary courses, institutions and their varying fee structures. present policy developments in australia regarding university fees will ensure that the cost of education in australia, along with its share of household expenditure, will continue to rise in coming years.

出处:melbourne institute working paper no. 11/02; issn 1328-4991; isbn 0 7340 1535 6 p1-p3,p9-p17